Living Organisms for Living Spaces: Shifting the function of the material by Juliana Silva 2018

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2112&context=tsaconf

Living Organisms for Living Spaces: Shifting the function of material

Juliana Silva Diaz

Abstract

This document explains the creative and analytical processes behind the project Living Organisms for Living Spaces. This art project examines the conceptual considerations around material by analyzing ‘objects’ – specifically fabric and textile ornaments – from Colombia’s material culture. The project explores the symbolic meaning of these objects that have both a Catholic and colonial legacy in society.

“To seek the symbolic potentialities of cloth in its material properties is, however, but a preliminary step, and only partially compelling. Equally important are the human actions that make cloth politically and socially salient.”

Jane Schneider and Annette B. Weiner

Cloth and Human Experience

Illustration 1: Home altar, art collection of Dominique Rodriguez Dalvard. From author’s collection.

The concept of ‘material’, as we understand it in the modern age stems from its proximity to the concept of ‘matter’. However, its philosophical meaning dates back to ancient times and is actually connected to the concept of ‘form’, as explained by professor and art historian, Monika Wagner. In addition, she says that in everyday applications, material is regarded as commonplace and is not highly valued. “In general, material, unlike matter, refers only to natural and artificial substances intended for further treatment […] In a narrower sense, material is the stuff which provides the parent substances for artistic creation.”[1] Thus, ‘material’ is usually understood simply as a means that exists to service form. Therefore, Wagner suggests that the understanding of ‘material’ as an ‘aesthetic category’ in itself is recent. In this sense, by using unconventional materials, contemporary artists have changed the very idea of material. These materials are charged with meaning and this meaning begins to play a valuable role in the work.

This document explains the creative and analytical processes through which the project Living Organisms for Living Spaces was realized. This art project examines the conceptual considerations around material by analyzing ‘objects’ – specifically fabric and textile ornaments – from Colombia’s material culture. Colombia is a country built on Catholic beliefs, thus the project explores the symbolic meaning of these objects that have both a Catholic and colonial legacy in society.

There are two concepts that underline this body of work: ‘Materiality’ and ‘The Uncanny’. In describing the art pieces, I intertwine the unfolded material reflection and the appropriation of the uncanny. This strategy transforms objects into something new, disrupting their prior meanings and functions.

The material approach begins with the vision of art historian, Edward Sullivan. His methodology is to investigate ‘objects’ “and use them as a starting point to discuss social, political, religious, and theoretical readings of their meanings”[2]. I appropriate this methodology for the visual arts. Textiles and ornaments all come under the umbrella of ‘objects’ and they are also my materials. In addition to understanding material culture on a symbolic level – where materiality offers a metaphor to unveil cultural transmissions, values, and beliefs – I am also attracted to textiles because of their intrinsic transformation qualities. Fabrics always have the potential to become something else. They are flat but can acquire multiple forms. They are also functional and serve many functions such clothing or household decoration, from curtains to tablecloths, blankets or upholstery. Primarily, fabrics are used for covering and protecting objects or the body.

On the other hand, I am captivated by religious imagery, which is very common, perhaps even ubiquitous, in decorating Colombian homes (See Illustration 1). I decide to explore Colombia’s Catholic background through an examination of materials such as velvet, gold threads, tassels, and lace. In doing so, I seek to delve into the subtle codes that are used to endorse power. The concept of the ‘The Uncanny’ is also a way of disrupting these codes of power. Umberto Eco’s book, On Ugliness, devotes a whole chapter to this theme, examining the ideas of Ernst Jentsch, and his essay, On the Psychology of the Uncanny. Eco says that Jentsch defined it as “something unusual, which causes ‘intellectual uncertainty’ and which we can’t ‘figure out’”[3]. Following that line of thought, the uncanny embodies both the familiar and unfamiliar.

By intertwining ideas of materiality into those of the uncanny, my artwork interrogates the transformation of fabrics throughout history, questioning legacies by shifting the function of the material.

Materiality is the entry point of my work. There is a fascination with the tactility of materials and the way in which one experiences that tactility visually as well as physically. This is particularly true for textiles and, in addition to their symbolic meanings, is another reason why I find them captivating. In my work, I deliberately use materials designed to serve a functional purpose in daily life. Each time I approach a textile in my practice I start to ask questions such as: Where is that fabric made? What is made for? Who wears it? Which fiber was used to make it? Why is it this color? In which context is it used? (See Illustration 2.) My research into these questions shows that the fabrics are a testimony to social transformation. It means that by analyzing humans’ interaction with textiles I am able to unravel the idiosyncrasies of a society.

Immersed in my research, I pay attention to velvet in reds, purples and greens. These colors remind me of the dresses on wooden statues of the Virgin Mary; of today’s upholstery in working-class homes; and of evening gowns popular among girls in Colombia (Illustration 3). I observe that the velvet has the same connotation in each of these incarnations: to cover an object or body and provide it with an aura of power and exclusivity. The aspirational or exclusive aspect catches my attention. Mass production means that today the cost of velvet is lower and so it has lost some of its exclusivity. Where then does this symbolic meaning of exclusivity come from? Historically, velvet’s high cost made it accessible only to nobility and the ecclesiastical community[4]. If velvet once signified royal and religious power – and still has some residual meaning – increasingly it has come to signify the loss of exclusivity due to the simplification of production.

Sullivan examines the material culture in Latin American society during the Colonial era to understand its circumstances and aspirations. Specifically, he analyzes paintings from this period that represent everyday objects and commodities – including textiles and ornaments. Among the artifacts that Sullivan looks at, I am particularly struck by the Andean paintings that depict wooden statues of the Virgin Mary and her dresses. One example is The Virgin Mary of the Cerro Rico of Potosi, (Unknown artist, oil on canvas, Bolivia, 18th century). The image combines a representation of the Cerro Rico in Potosi, Bolivia with the face of the Virgin Mary while the dress hides the mountain (Cerro Rico) that the native people used to worship. The Virgin’s red dress seems to be velvet and the skirt depicts both clothing and mountain at the same time. Another example is Our Lady of the Rosary of Pomata, (Unknown artist, Cuzco, Oil on Canvas, 18thCentury), which is rich in patterning and ornamentation (See Illustration 4).

Illustration 4: Our Lady of the Rosary of Pomata, art collection of Colonial Museum, Bogota. From author’s collection.

These depictions remind me of the religious iconography that surrounded me in my childhood, such as depictions of Jesus in the Passion Narratives. I have memories of anthropomorphic figures carved in wood and covered with gold; of people carrying statues of the Virgin Mary adorned not only with clothing made from velvet and threads of gold, but also with human hair and glass eyes to enhance their physicality; of processions of penitents wearing purple robes and conical purple hats that covered their faces; and of the white and black veils worn by women at church services. These and other symbolic representations embedded in the culture were on full display, especially during the ritual processions at Easter (See Illustration 5).

Illustration 5: Saint Ecce Homo during The Holy Week Procession, Popayan, Colombia. From Policia Nacional de Colombia’s collection.

These memories turn into curiosity and a fascination with fabric that drives my artistic investigations. For example, I focus my attention on velvet because of its colonial legacy. Its introduction in Latin America began with the exposure of indigenous people to Catholicism. The Catholic Church was one of the most important consumers of sumptuary objects, and velvet was highly sought after. Velvet’s complex production process made it expensive and only affordable for the elites.

The work Specimens (See Illustration 6) emerged from this research into fabric. This is a series of photographs of hand-made ‘stuffed’ objects, covered with polyester velvet and drapery mesh. I made velvet spheres, wrapped in a grid of green mesh. Gold threads grow from some of the spheres giving the appearance of hair follicles. In Specimens, I seek to disrupt the connotation and function of the fabrics. Most of my materials selection examines the old symbols of power and wealth inherited from the Catholic institution that permeated the domestic atmosphere. I pay particular attention to materials that infiltrate domestic situations because I consider that the domesticity trivializes them.

In search of disruption, I find the concept of ‘The Uncanny’, an idea that I appropriate to develop my work. I am intrigued by Eco’s exploration of objects that trigger a sense of so-called intellectual uncertainty – “something that isn’t going the way that it should.” Rather than rejecting the uncanny, I seek to develop a level of curiosity about it. The ambiguity of familiarity and unfamiliarity simultaneously produces discomfort – because that object does not fit into a recognizable category. I am interested in the liminal places, on the borders where it is hard to categorize, name and order (See Illustration 7).

Illustration 7: Illustration 8. Fungi, drapery lace, golden taffeta, dimensions variable, 2017. From author’s collection.

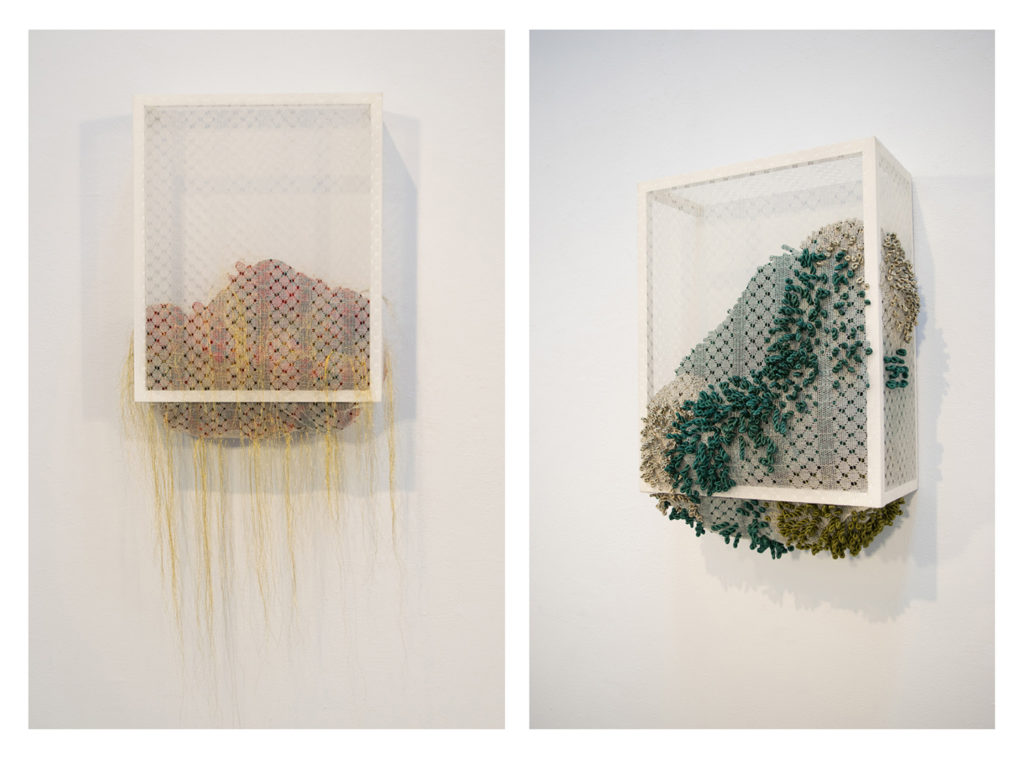

This idea of ‘The Uncanny’ is more evident in the work Anomalies (See Illustration 8). Anomalies is a set of two boxes wrapped with drapery lace positioned on the wall. The boxes contain objects made from both fabrics and garments. The first contains objects made out of red velvet and gold threads which hang out of the box; the second contains pieces made from green tassels that are pulled through the mesh of the lace. In both boxes the objects suggest that they want to grow and exceed the limits of their containers, which also deforms the containers themselves.

My intention was to create pieces that generate a certain familiarity: while the final form causes confusion, the treatment of the materials still allows the viewer to recognize them. The lace was placed deliberately to challenge the view of what is inside.

Gestures applied to the pieces, such as the tumors that deform the boxes or the material that is pulled out through the mesh, became actions that alter perceptions. These gestures are an invitation to re-evaluate cultural borders and re-think our bodies in terms of what is included and what is excluded.

Illustration 8: Anomalies, drapery lace, fringe, wood structure, 21”x17”x8”, 2017. From author’s collection.

The way the materials are purposefully transformed reveals subtle acts of domination, resistance, and ultimately negotiation, all of which are underlined in culture. I decided to give voice to the materials, they are artifacts that become witnesses, and they are present in our daily lives and in our domesticity. Materials are observers of the exchange between subjects and objects; they allow me to speak about what is unnoticed because they are deeply rooted, silent, and potent.

The Living Organisms for Living Spaces project is a commentary about containment, domination, and domestication. The creatures inside the boxes are expanding beyond the limits of the containers that house them. There is a subtle violence between the content and the container: forces are colliding and merging. The lace that establishes the limits is both stretching and resisting – the pieces inside are coming out and pushing the border of the container. Living Organisms for Living Spaces gives us a taste of abnormality in the safe surrounding of our own living rooms.

Notes

[1] Wagner, Monika. “Material.” Lange-Berndt, Petra. Materiality. 26

2 Sullivan, Edward J. The Language of Objects in the Art of the Americas. XVI

3 Eco, Umberto. On Ugliness. 311

4 Peck, Amelia. Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800. 2013.

Bibliography

Eco, Umberto. “Lowbrow Highbrow, Highbrow Lowbrow.” Ed. Carol Anne Runyon Mahsun.

Pop Art: The Critical Dialogue. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Pr., 1989. 221-31. Print.

—, Umberto. On Ugliness. New York: Rizzoli, 2011. Print.

Lange-Berndt, Petra. Materiality. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2015. Print.

León De La Barra, Pablo. “Under De Same Sun: Art from Latin American Today.” (n.d.): n. Web. 28 Apr. 2016

Peck, Amelia. Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800. n.p.: New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, [2013], 2013.

Sullivan, Edward J. The Language of Objects in the Art of the Americas. New Haven: Yale UP, 2007. Print.

Wagner, Monika. “Material.” Lange-Berndt, Petra. Materiality. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2015. Print.

[1] Wagner, Monika. “Material.” Lange-Berndt, Petra. Materiality. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2015. Print, 26

[2] Sullivan, Edward J. The Language of Objects in the Art of the Americas. New Haven: Yale UP, 2007. Print. XVI

[3] Eco, Umberto. On Ugliness. New York: Rizzoli, 2011. Print. 311

[4] Peck, Amelia. Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800. n.p.: New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.